In association with DO Jumilla.

Perfectly suited to the climate and growing conditions of Spain’s high plateau, the Monastrell grape is revered by Jumilla’s winemakers – and a new generation is pioneering the evolution of expressive modern styles.

Elena Pacheco freely admits that a couple of decades ago, she and many of her young winemaking colleagues in Jumilla were tempted to replant their vineyards with fashionable French grape varieties. But those days are long gone. The 12m-long vine, suspended from the roof of her Viña Elena winery as an exhibit, is of course the native Monastrell, a grape variety that today covers almost three-quarters of the Jumilla vineyard.

Monastrell’s long vine roots are one reason why Jumilla’s growers revere it. They’re able to delve down into the region’s rocky, limestone soils to extract all the moisture the plant needs, even during Jumilla’s long, baking summers. This is no recent discovery: generations ago, farmers here devoted what water they had to their olive groves and almond trees, knowing that their vines could manage without. This ancestral knowledge is perhaps why in Jumilla, one of the driest areas of Spain, most vineyards are still dry-farmed.

Monastrell has a long drawn-out vine cycle. ‘This has the great advantage,’ says winemaker Valérie Durand, ‘of grapes ripening when the nights are cooler, thus preserving acidity and allowing complete phenolic ripeness.’

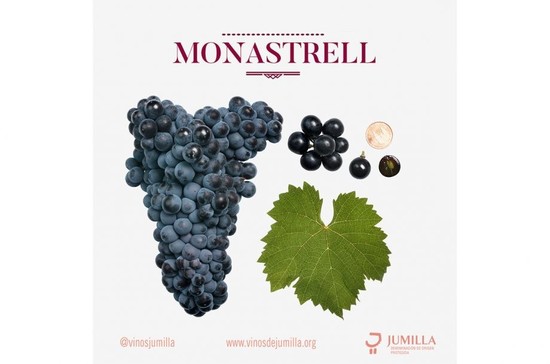

Despite its virtues, Monastrell can be tricky to grow. Its bunches are small and very compact, resulting sometimes in varying levels of berry ripeness on a single bunch, making careful sorting essential. The skins are thick, and can remain tough well into October. Good extractability of tannins is key, and so harvesting dates can be crucial.

Speaking to Jumilla’s producers, you sense regret that in the past not enough was done to promote their terroir and beloved variety. Monastrell was often bought by merchants to strengthen the colour or body of their blends, and growers didn’t always exploit the potential of the raw material, either in the vineyard or the cellars.

Fortunately, Jumilla’s new generation of producers has brought an exciting new impetus. Rustic Monastrell with prune notes has made way for wines vinified from dry-farmed vineyards that express pure red berry fruit aromatics (plums and black cherries), balance, flesh, abundant silky tannins, minerality, liquorice and a characteristic touch of bitterness in the finish that adds to the appeal.

Jumilla’s unoaked or lightly-oaked reds can be deliciously fruity and refreshing with surprising complexity and length on the palate. Judicious oak ageing is crucial at the higher end. As Pacheco points out: ‘Monastrell doesn’t need much oak. It ages better in larger capacity barrels or foudres.’

While it can excel as a monovarietal wine, Monastrell blends well with certain adapted varieties. Emblematic winery Juan Gil, situated at 700m altitude, combines a generous proportion of Cabernet Sauvignon, while Silvano Garcia, at 500m, opts for the youthful fruit character of Syrah. ‘Both Cabernet and Syrah are great dancing partners for Monastrell,’ says BSI’s Alfonso Hernandez, ‘but it’s as a soloist that it performs best.’

Unquestionably, choice of variety is driven by terroir rather than marketing. Monastrell-lovers can rest assured that those fashionable invaders of a generation ago will only ever play second fiddle in Jumilla.

Translated by Leo / 孔祥鑫

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit