Have you ever thought about associating winemaking with Chinese kung fu? Such as the style of old-vine Shiraz from Australia? Read Terry Xu's thoughts on the characters of classic Australia red wines.

A while ago I took part in a masterclass organised by the official trade body Wine Australia. Within two hours, Andrew Caillard MW, the co-creater of Langton's Classification system, guided us through a tasting of 13 collection-worthy, top Australian wines, including the famous Penfolds Grange.

The stereotype

I don’t need to tell you how much I enjoyed these wines. I’d like to talk about a stereotype people—including me—tend to think of Australian wines, that they are ‘always somewhat similar’ to each other. People tend to think that judging from the wines they can find in China, many wineries haven’t established their own unique features.

Be it Shiraz, Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, the ultimate target of Australian winemakers seemed to be the same: Riper, denser and more powerful.

As a wine professional, I can easily argue against such nonsense with evidence on the climate, soil and winemaking skills. However, would consumers appreciate the lengthy explanations? And to be honest, are we Chinese professionals fully convinced ourselves that these wines are ‘that different’ from each other?

The edges and corners

At this particular tasting, however, I am most definitely convinced. I saw the ‘edges and corners’ of Australian wines through the tasting, and my overall impression on Australian wines has changed from a ‘ball (round and even)’ to a ‘hedgehog (zigzagged and with many extremes)’.

The Cabernet Sauvignon from Yeringberg, to begin with, was delicate, elegant and earthy; the Cabernet from Petaluma of Coonawarra, however, was tender, complex and layered; the Howard Park Abercrombie version of the same variety was athletic and masculine, with great aging potential.

Each wine had its own features, and was difficult to associate with the Cabernets from any other region or country (especially Bordeaux). The tannin structures may come from old vines or winemaking, but the same level of precision reminded me of the Chinese Tai Chi, a type of martial art known for some of its slow but flexible and clever moves.

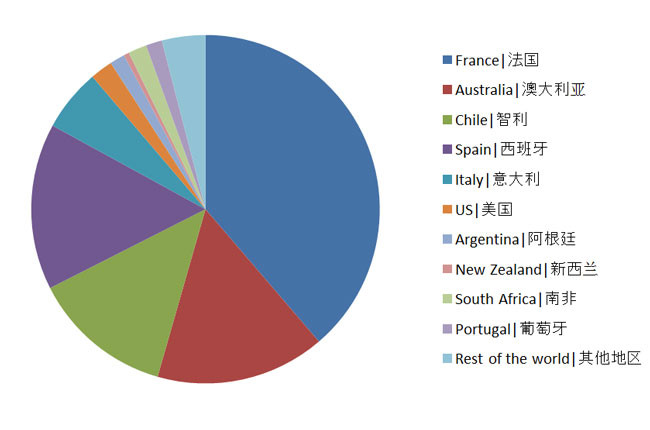

Australia’s treasured grape variety, Shiraz, showed very high average quality at the tasting. It was by no means easy for these wines to excel among the many ‘Kung Fu masters’ -- successful Shiraz from the other countries -- which consumers can already find in the market.

Judging from the few Australian wines presented at the tasting, at least, my impression is that winemaker in Australia is gradually releasing their ‘control’ on these wines. In other words, they’re aiming for a more natural style.

Every wine had a thick and dense core, but wrapped with layers flower, chocolate, pepper, spice, bacon and earth. Again just like Tai Chi—they are light on the touch but weighty at heart, soft on the surface but powerful when you swallow.

The influence of old vines

Such styles must have something to do with the characters brought by the old vines, I suspect. At least that’s the case for the wines we have tasted: Graveyard Vineyard from Brokenwood, Eileen Hardy of Hardy’s, 1860 Vines of Tahbilk, The Eagle of Dalwhinnie, Old Block of St Hallet and finally Freedom of Langmeil.

All these Shirazes, in my opinion, were equipped with the most precious and not replicable weapon in the world: time. There’s simply no need for excessive actions in the winery, yet these wines thrive with the gift of time.

Sword master Feng Qing Yang (‘drifting wind’) in Chinese novelist Jin Yong’s famous Swordsman once said: the way of the sword is the way of nature, it should be smooth and unstoppable like a flowing cloud in the wind, or the water in the stream.

Maybe master Feng was spot-on about the winemaking philosophy of Australian old vine Shiraz: the somehow casual style is engraved with the time accumulated in the vines, making each wine impossible to replicate. They are almost mysterious—even the winemakers don’t know what does time have to offer, how can they make ‘similar’ wines at the end?

The only wine that still left me wonder was the Dead Arm Shiraz from d’Arenberg —it was as strong and powerful as always, like a heavy push from a hard-muscled man. What Kung Fu is this? Will you ask dear Chester Osborn for me when you see him next time?

Translated by Sylvia Wu / 吴嘉溦

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit