We’re a lucky lot: the last three decades have brought a high renaissance to the wine world. A century of wars, depressions and crises followed phylloxera. The renaissance was a long time coming.

Beginning in the 1980s, huge technical advances in winemaking coincided with a warming world and its generous vintages. A peaceful and rapidly developing global economic scene meant a lake of middle-class consumers around the world, eager to reward wine-making endeavour. The luxury triggers in wine proliferated. Every dream beckoned. The number of places in which ambitious wine was made outside Europe rapidly increased.

A renaissance, as students of literature, art and music will know, is a time of exciting stylistic experiment. So with wine. Some wanted to make the biggest wine in the world, or the most concentrated. Others pursued different ideals: the darkest, the fruitiest, the oakiest, the tightest, the sharpest, the crispest — or the smoothest and softest; even, indeed, the most sweetly ‘dry’. The culture of the critical score set everyone chasing superlatives. These three decades of exploration and experiment, of boundary-pushing, of ‘statements’ and of ‘icons’ gave us an exuberant cacophony of styles. I’ve wandered wine roads for 30 years, and have often marveled at the way in which no two wine producers ever seem to work in exactly the same way. The finest producers of a single region, indeed, often take diametrically opposed approaches, yet the results produced by each are outstanding. Certain style questions seem beyond arbitration.

Or seemed so, until recently. Now there is a kind of aesthetic coalescence in the wine world which I hadn’t expected. The mists are clearing a little, and we can make out some kind of a landmark atop a hill. It does not mean an end to diversity; indeed in a way it is the only route to diversity. That landmark is purity.

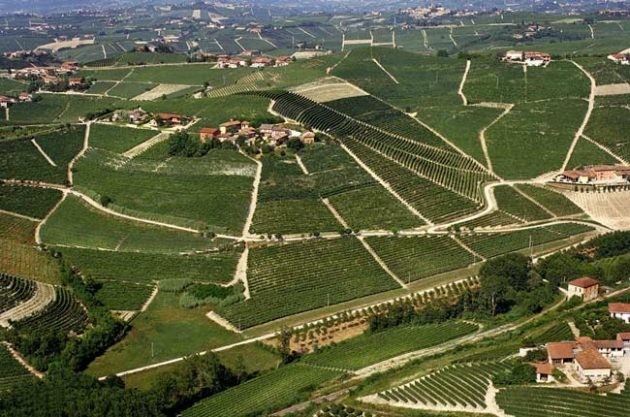

I think this unspoken accord has come about through the acceptance, wherever ambitious wine is made, that the pursuit of terroir is essential. Why so? Because terroir – a sensorial expression in wine of the personality of place, interpreted by appropriate varieties and sensitive winemaking — is the key to sustainability for high-quality fine wine. Everything else can be imitated or duplicated. Not, though, your place on earth.

The renaissance cacophony has taught us how easily obscured the taste of a place might be. We came to see that the pursuit of the superlative often resulted in winemaking which was a kind of swaddling or covering up. In the pursuit of ‘more’, we ended with ‘too much’. Yet when we tasted the old classics, we could see that what was really required was an uncovering, a revelation. What should be revealed is the complexity, balance and beauty latent in harvested fruit; the winemaking challenge is how best to set that off, as a jeweler might set a precious stone. Too strenuous a setting suffocates the jewel. Hence the new desiderata: purity and limpidity. And in practice?

Let’s begin with berries. They don’t need to be overripe to bring pleasure – but underripeness is not an appropriate response to warming seasons, either, since an underripe grape is one which has not yet found its full voice. The perfectly grown berry picked on the perfectly ripe day is the ideal; fruit-sorting machines are a great breakthrough. The season lies inside the undamaged berry and its skins, written out like a secret message. (Damaged berries deliver error messages.)

What of whole bunches or clusters in the vinification of red wines? Much depends on the variety, of course, yet many of those most consciously pursuing purity in wine are believers in the ideal of whole-bunch fermentation for red wines; stems, the theory runs, can express terroir too, and there are advantages in terms of the architecture of the marc and the prolongation of fermentation. In warming times, many feel that some stems in fermentation bring freshness. All red wines, too, were once ‘whole bunch’ – since the destemmer was a post-phylloxera invention. We will certainly see more whole-bunch fermented reds in the future — yet there are compelling arguments on both sides. Stems, after all, are not fruit. Should pure wines not be pure fruit?

Much has changed, too, in terms of the way red-wine fermentations are conducted. Wine’s high renaissance was often a time of exuberant extraction for red wines, though we came to realise that that made for rather noisy and sometimes denatured wines, especially in regions like Burgundy or Barolo where a desired delicacy of tone was easily lost. The quest for purity means that extraction has often given way to infusion, or something very like. Assuming that the fruit is perfectly ripe, this need not mean any loss of structure.

he picture for white wines is more complicated, since too much determination in the quest for a steely, reductive purity left certain wines open to the depradations of premox. There are, though, other routes to purity. The issue of lees is in some ways analogous to that of whole bunch for reds; lees, too, are an intimate part of a wine which it might be illogical to discard too soon. Oxidation itself is a complex question, since much depends on exactly when the must or wine is exposed to oxygen, and whether or not sulphur has been used. Drinkers should trust their senses on this, and keep an open mind.

What all agree on is that there was too much recourse to new oak during the high renaissance; the retreat is now universal. As a result, cellars are now much more entertaining than they used to be, since you never know what’s hiding just around the corner: giant clay jars, sinuous new concrete tanks, gleamingly large wooden casks, concrete eggs, wooden eggs, steel barrels, glass jars … or, quite simply, wooden barrels which have seen more use than was formerly the case. “The solution to too much oak,” said one Spanish winemaker to me recently, “is not no oak.”

As the details above indicate, purity is in fact the common thread which links the ‘natural’ wine movement with the fine-wine avant-garde in classic regions like Bordeaux or Burgundy. It is a shared ideal, the only point of difference being a degree of dogma regarding sulphur, and what one might call ‘a habit of tasting’. If you are crafting 2015 Ch Palmer, now on sale for £250 a bottle, you must taste to the highest sensorial standards, and be alert to any note which might be construed as deviation; whereas natural winemakers selling £20 bottles cut their wines more slack, and accord ‘moral probity’ higher importance than pristine sensual refinement (as do their customers). Otherwise, we are all purists now.

Have we, therefore, reached the ‘end of history’? No: history never ends, and there will be more shocks ahead requiring extraordinary responses. Climate change is likely to weigh more and more heavily on those seeking to maintain the expressive force of great vineyards, and varietal changes in the years ahead in order to respond to climate change cannot be ruled out; grapevine trunk disease, too, is going to change wine-making economics to increasingly dramatic effect. Our wine world will be a very different place in 100 years.

We can, though, say that wine’s high renaissance is concluding with a kind of philosophical unification: that purity in wine is the highest ideal of all.

Translated by Sylvia Wu / 吴嘉溦

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit