As a wine educator, I find it very frustrating how some myths can live on for so long, sometimes even among wine professionals. One of these common misconceptions is the cork’s relationship with incoming oxygen.

Two years ago, I met with my fellow wine educators to discuss a new wine course. The course was developed in France by specialists of the industry, and double-checked by professionals dedicated to wine education. Despite the undoubtedly reliable background of the authors, an erroneous and contradictory assertion found its way into the PowerPoint slides:

‘For red wines, the cork’s objective is to let some oxygen enter the bottle in order to encourage maturation. For white wines, the cork’s objective is to prevent oxygen from entering the bottle in order to retain its freshness as long as possible.’

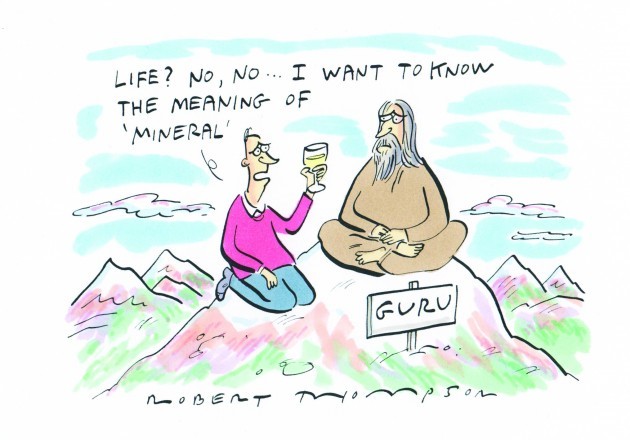

Although I am curious to find out how the cork determines the colour of wine, the point which bothers me the most is the fact that still today, people think that red wine needs to ‘breathe’ through the cork in order to evolve.

In the late 19th Century, Louis Pasteur rightly pointed out that ‘oxygen is wine’s worst enemy’. To be more precise, I would add that oxygen is wine’s worst enemy after bottling; considering that some oxygen input is often useful, if not essential, for the transformation of the grape juice into our beloved wine. Once the wine bottled, a sustained oxygen influx will only urge the wine towards its death. Any sound winemaker, regardless of their wine’s market position, will do everything they can to delay the fading away of aromas and flavours. I never heard a winemaker wishing to see some air entering a wine that they had bottled!

When I visited Domaine Paul Blanck in Alsace a few years ago, I remember Frédéric Blanck emphasising that wine matures naturally in an anaerobic environment, and the belief that it needs oxygen to mature is a myth. In fact, the reason why people started to use cork to seal bottles back in the 18th Century was because of this material’s natural elasticity and impermeability, which made it the most efficient barrier against external air. Today cork is still widely used for its excellent airtight properties, even though alternatives such as screw caps can match or even surpass its efficiency.

Another question might occur to DecanterChina’s readers:

‘If wine doesn’t ‘need’ oxygen to evolve, doesn’t the colour-changed and altered aromas in aged wines indicate that some air still gets in the bottle?’

Yes, some air does enter the wine from the cork, but not through the cork. Dr. Paulo Lopes, who has conducted various academic studies with the University of Bordeaux about closures and oxygen ingress, points out that a natural cork stopper is made up of 80% to 90% air, and it is actually this air (and the oxygen it contains) which is gradually released into the wine, especially during the first three years of its life. After this period, the oxygen transmission rate (OTR) becomes negligible, almost similar to that of screw caps, and even after eight years, the oxygen content in a wine sealed under high quality cork remains stable. Wine eventually oxidises not because the air passes ‘through’ the cork, but because the cork loses its elasticity, giving way to atmospheric air via its sides.

According to Dr. Lopes, the pace of the oxidative evolution after the first two or three years depends greatly on the quantity of oxygen which has been released by the cork, and dissolved into the wine during the first years. The research report ‘Impact of Storage Position on Oxygen Ingress through Different Closures into Wine Bottles*’ written by Lopes and fellow researchers in 2006 shows that a higher quality ‘flor level’ cork containing fewer lenticels (pores) will release less oxygen during the first years. Dr. Lopes explains that the slower evolution of a wine sealed with a flor-grade cork is partly due to the lesser quantity of oxygen released at the beginning of its ageing in bottle. In other words, even after ten years ageing, your Grand Cru Classe’s oxidative evolution has more to do with the quantity of oxygen released by the cork during its youth — rather than because of a supposed exchange between the bottle and its external environment.

Research is still going on, and new discoveries are expected soon, particularly about the impact of phenolic compounds contained within the cork on the oxidation and reduction of the wine. Of course, I will make sure to let you know about these when the time has come. Meanwhile, keep you corks moist!

*Read the research paper here.

Translated by Sylvia Wu / 吴嘉溦

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit