Andrew Jefford discovers the unexpected after taking a closer look at the divide between Barbaresco and Barolo.

What exactly is the relationship between Barolo and Barbaresco? The Bordeaux model of Left and Right Bank isn’t echoed here, since there is no varietal difference between the two DOCGs: it’s nothing but Nebbiolo. Perhaps the contrasting red wines of the Côtes de Nuits and the Côtes de Beaune are a better comparison: they offer a subtle difference in style based on a modulation of topography and soils. When you peer more deeply into this question, though, there are surprises in store.

Langhe fans are sometimes startled to discover that Barolo and Barbaresco are not adjacent zones. They are separated by the town of Alba and by much of the Dolcetto-growing zone of Diano d’Alba (which also pokes into Barolo). Barbera d’Alba, too, can be grown in these transitional vineyards – but this enormous DOC also covers Barolo and Barbaresco in their entirety and much else beyond.

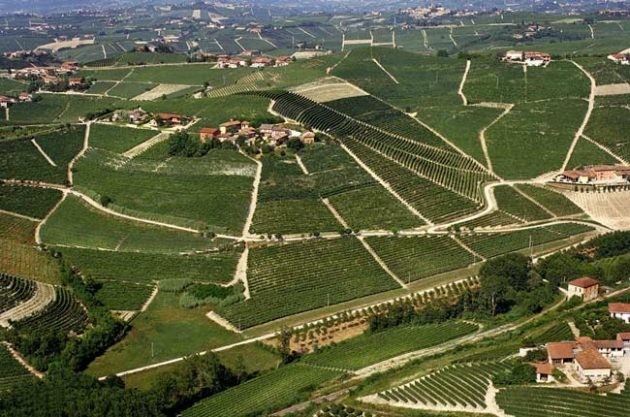

There are useful lessons here. Both Barolo and Barbaresco are, in fact, comprehensively planted with varieties other than Nebbiolo; the villages of Neive and Treiso within Barbaresco constitute a key Moscato d’Asti-growing zone, for example, into which Nebbiolo has only begun to make inroads in recent years. One look at the chaotic topography of the region and you will realise that this has to be so. It’s a comprehensive contrast to the Côte d’Or.

In fact what the Barolo and Barbaresco zones signal is that the greatest sites for Nebbiolo in the Langhe are found somewhere or other within their boundaries: they encircle Nebbiolo hot-spots, if you like. Barolo is the hot-spot southwest of Alba, and Barbaresco is the hot-spot northeast of Alba.

How hot? My assumption had always been that Barolo was the warmer of the two, and probably the lower lying, based on the fact that its tannins were grippier, its fruit more forceful, and its ageing requirements more imperative.

Wrong again. Barbaresco is in fact lower, warmer, and usually harvests earlier. The highest vineyard sites in La Morra and Monforte lie just above and just below 550 m, while Serralunga peaks at 450 m. Barbaresco, by contrast, has no site higher than 500 m, and most great sites peak at 300 m or so. It’s perfectly common in Barolo for Nebbiolo to be growing at 400 m.

There are other physical differences, too. Barolo, lying further west, is hit by weather systems prior to Barbaresco, which enjoys a more sheltered position. This factor made a dramatic difference in the 2014 vintage, when Barolo wrestled with a total of 1,400 mm of rain while Barbaresco strolled by with just 750 mm.

That still doesn’t explain the style difference, though, between Barbaresco’s gentleness, elegance and approachability and Barolo’s force and power. Maybe it’s all in the soil? Once again, our theorising seems frustrated: the limey blue-grey Sant’ Agata fossil marls and the slightly sandier or siltier Lequio formation marls dominate both zones.

Let’s head back to the map again. Remember that the best and most Nebbiolo-friendly vineyards in Barbaresco are in the village of Barbaresco itself. Take a look where that is: on a series of rising and falling bluffs, up above the river Tànaro. Australian Dave Fletcher, who lives and makes wine in Barbaresco, says that its ‘golden mile’ is the proportion of the zone which runs along the river. Barolo, by contrast, lies in its own little bowl of hills, south of the Tànaro. There is only one Barolo village close to the Tànaro, and that is Verduno – often said to be the most ‘Barbaresco-like’ of all Barolo villages. Could this be a clue?

Now we might be getting somewhere. Barbaresco growers often talk about an ‘air-conditioning’ effect brought by the river – it’s breezier and less prone to storms, even though the summations show it to be warmer on aggregate. Look, too, at the shape of the main ridge lines in both Barolo and Barbaresco (not easy for the untrained eye, I admit), and you’ll see that Barbaresco’s key sites tend to be west- or east-facing, whereas Barolo has a much higher percentage of south-facing sites. Both of these are surely significant factors.

When you talk to the locals, too, it would seem that soil differences do indeed play a role, in that Barbaresco soils tend to be somewhat sandier, softer and warmer than Barolo soils, even though the formations are the same. The Lequio formation in Serralunga, for example, contains less than 20 per cent sand, whereas the same formation in Treiso and Neive contains about 30 per cent sand. And in general the Langhe soils tend to get sandier as they approach the Tànaro; Roero, on the north side of the river opposite the village of Barbaresco, is almost pure sand. More sand means less clay in the mix, and less clay will tend to mean less retained water – which in turn is critically important for polyphenolic development.

So that’s my provisional answer to the question as to why Barbaresco differs from Barolo: proximity of the river, aspect of the main slopes and percentages of sand in the soil.

What drinkers rather than wine students should remember, though, is that we are not talking about ‘better’ and ‘worse’ here; we are talking about ‘different’. The virtues of the finest Langhe Nebbiolo – its detail, its refinement, its grace, the brightness of its balances, and its tannic generosity (with all that implies for health, digestibility and gastronomic aptitude) — are shared by both wines. Even if Barolo didn’t exist, Barbaresco would still be up there with the world’s greatest red wines.

Translated by ICY

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit