Jane Anson writes about Thomas Jefferson's influence on Bordeaux during his brief time in the city and includes a cautionary tale from later in Jefferson's life when he pursued an America First-style policy as the third US president.

As the United States prepares – as much as anything is clear right now – to implement its America First policy, this is perhaps a good week to look at one of the most Europe-friendly of all previous commanders-in-chief; Thomas Jefferson, the third president of America from 1801 to 1809.

And why perhaps we should temper our enthusiasm for his achievements.

Jefferson in Bordeaux

There isn’t a statue of Jefferson in Bordeaux, and nor are there any roads named after him, but he undoubtedly made a contribution to the history of this city. If you look, you’ll find a couple of commemorative plaques, most notably on the wall of the US Consulate that celebrates him as a ‘symbol of French-American friendship’. As of March 13 2015, a Thomas Jefferson jetty was inaugurated along the Garonne river on the Chartrons quayside, and the Cité du Vin has a Thomas Jefferson auditorium.

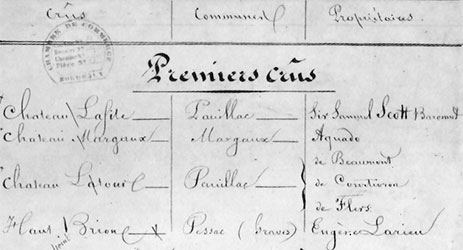

The jetty is particularly appropriate, as Bordeaux was one of the key departure points for French sailors heading off to fight in the American War of Independence – the Marquis de Lafayette himself set sail from Pauillac in 1777. But the city’s claims to Jefferson as a symbol of its wine are maybe a little more tenuous, as it turns out that he only spent five days here during the entire four years, from 1784 to 1789, that he was in Paris as Ambassador to France. In fact perhaps more credit should be given instead to John Adams, second president, who discovered « First Grouths » of wines when he visited Bordeaux in 1778, nine years before Jefferson spent time here.

He even beat Jefferson to noting down the future First Growths, reportedly meeting a negociant called JC Champagne at Blaye on April 1, 1778, who told him about the four best wines of the region. Adams wrote, ‘of the first Grouths of Wine, in the Province of Guienne… Chateau Margeaux, Hautbrion, La Fitte, and Latour’. Almost two years later in April 1780, John Adams wrote from Paris to John Bondfield, the American commercial agent in Bordeaux, that he had ‘Occasion for a Cask of Bordeaux Wine, of the very best Quality”. Apparently he was particularly fond of Saint Emilion’s Chateau Canon, making him a man of extremely good taste in my book.

However, it is Jefferson who stands as a symbol of this American love affair with Bordeaux. The best account given of his short but action-packed visit to Bordeaux comes care of Bernard Ginestet in Thomas Jefferson à Bordeaux. Born in 1936, besides being an important negociant and chateau owner (including Chateau Margaux from 1950 to 1977), Ginestet wrote widely throughout his life. He published his first essay in 1971, aged 35, and his first novel aged 49 in 1986. They make excellently gossipy reading, and I totally recommend his take on the profession of courtiers through the barely made-up character of Edouard Minton in Les Chartrons.

Anyway, back to Jefferson. Ginestet covers in great detail Jefferson travels around European vineyards, not just Bordeaux, but he also provides fascinating background to what Bordeaux was like at the time, as seen through the eyes of locals and other travellers to the region.

Jefferson arrived in Bordeaux on Thursday May 24th, 1787, arriving from Langon in the south of the region, where he visited Chateau d’Yquem and Chateau Carbonnieux (‘de Carbonius’ as he wrote it). When he got to Bordeaux itself he stayed at the Hotel de Richelieu. Not easy to recreate this, as the original building is now a fast food place near to Galleries Lafayette, but it stood just a few minutes stroll from the Grand Theatre opera house, which had opened only seven years earlier.

According to Ginestet, Jefferson headed out on Friday 24th to Chateau Haut-Brion in Pessac (apparently he first drank this wine at Benjamin Franklin’s table – his predecessor as Ambassador to France) and what is now Chateau Pontac Monplaisir in Villenave d’Ornon. Saturday was spent writing letters, meeting people and watching two performances at the Grand Theatre, one after the other, as was typical at the time (that particular day was a tragedy by Voltaire followed by a more lively comic opera by Desfontaines et Dalayrac). Sunday 26th he got some money from his bank to pay for laundry and lodgings, and Monday he had a large breakfast with guests, then paid his bill and headed off on a boat to Blaye.

His diaries show detailed recordings of the vineyards and wines that he tried (and say almost nothing about what the hotel was like, or what dinners he attended, showing firmly where his interest lay – although some of his guests did help us out by recording these). At some point during the visit, he also placed orders for Yquem (the exact amount is not recorded), Haut-Brion (24 cases) and Lafite (250 bottles). The flow of Bordeaux wine to the States was well and truly in place.

Jefferson and the ill-fated Embargo Act of 1807

There is a corollary to all this, however. I looked up Jefferson’s foreign policy, and it turns out that although it dominated much of his time in office, he wasn’t averse to putting America first either. He was the first president to commit US forces to a foreign war (in Tripoli against pirates, rather excitingly). His friendship with the French then came in handy as Napoleon sold him the entire Louisiana territory in 1803 – basically much of today’s Midwest – for US$15 million, thus doubling the size of the United States without going to war.

Things went a little downhill from there, and might stop us holding up Jefferson as a champion of an outward-looking America – although to be fair it was England and France causing trouble again by endless wars. Jefferson tried at first to find a way to keep trading with both sides, but wasn’t able to in the face of reported British and French military attacks on American merchant vessel.

So he went to the other extreme and passed the Embargo Act in 1807 that prohibited all American trade with either Britain or France.

The result was a collapse in the number of American ships entering French ports, especially Bordeaux, according to figures published in a 2014 study by Silvia Marzagalli, in the Kyoto Sangyo University Economic Review.

American exports overall plummeted from US$108 million to US$22 million and large parts of the country were brought to their knees. Jefferson ended the policy in the last few weeks of his presidency in March 1809, but it’s fair to say this was a low point of US foreign relations.

Let’s hope they don’t get any lower.

Translated by Liu Xiang / 留香

All rights reserved by Future plc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of Decanter.

Only Official Media Partners (see About us) of DecanterChina.com may republish part of the content from the site without prior permission under strict Terms & Conditions. Contact china@decanter.com to learn about how to become an Official Media Partner of DecanterChina.com.

Comments

Submit